Data: Problems Inherent in Egg Production

The data, sources, and calculations used in the Problems Inherent in Egg Production infographic

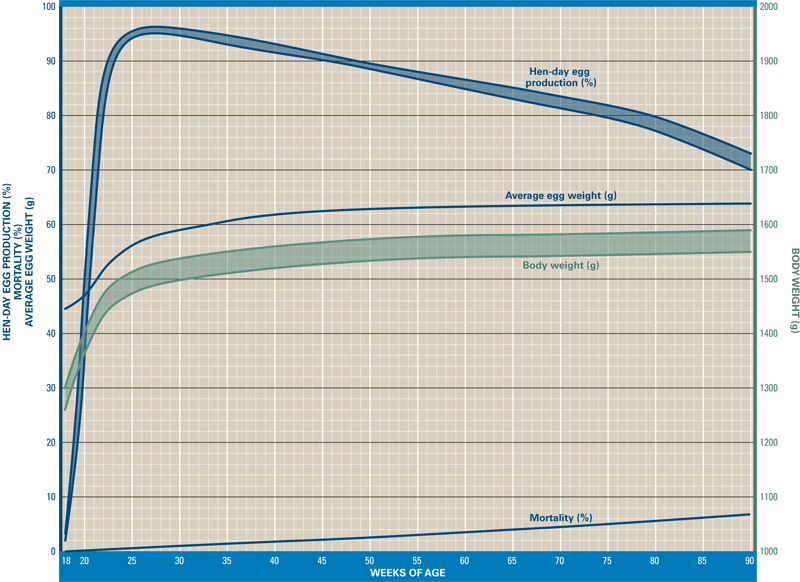

Egg Production by Age

Natural Lifespan

"On most commercial egg farms, laying hens have completed their usefulness when they are 18 to 20 months old. Records show that when chickens are allowed to live out their lives naturally, many of them will live in the range of six to ten years, and some claims have been made of some chickens living as long as 22 years."

"Many chickens will live over 5 years, some 8 to 10 years. ... Commercial poultry farms slaughter (or sell / re-home) hens at 18 to 24 months of age because they are no longer viable commercially."

Chick Culling

In the U.S., there are no federal legal restrictions on the methods of culling due to poultry's exclusion from the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act (HMSA)."Maceration, via use of a specially designed mechanical apparatus having rotating blades or projections, causes immediate fragmentation and death of newly hatched poultry and embryonated eggs. A review by the American Association of Avian Pathologists of the use of commercially available macerators for euthanasia of chicks, poults, and pipped eggs indicates that death by maceration in poultry up to 72 hours old occurs immediately with minimal pain and distress. Maceration is an alternative to the use of CO2 for euthanasia of poultry up to 72 hours old. Maceration is believed to be equivalent to cervical dislocation and cranial compression as to time to death, and is considered to be an acceptable means of euthanasia for newly hatched poultry by the Federation of Animal Science Societies, Agriculture Canada, World Organisation for Animal Health, and European Council."

"HMSA covers livestock animals, such as cattle, calves, horses, mules, sheep, swine, and "other livestock," which has been interpreted to include goats and "other equines." Poultry animals (domestic birds) have been excluded from HMSA's protection."

Number of Layer Hens Killed Per Year

Number Slaughtered, Lost, and Added During the Month — United States: 2013-2014 Month Layers sold for slaughter Layers rendered, died,

destroyed, composted, or

disappeared for any other reason

(other than sold)Pullets added 2013 2014 2013 2014 2013 2014 December 13,451,000 14,156,000 7,882,000 7,573,000 21,907,000 23,722,000 January 15,629,000 15,707,000 7,582,000 8,222,000 24,992,000 22,821,000 February 13,696,000 15,877,000 6,847,000 8,244,000 23,524,000 24,543,000 March 13,508,000 13,410,000 7,085,000 7,895,000 25,178,000 24,201,000 April 18,128,000 14,441,000 7,843,000 6,942,000 22,953,000 24,222,000 May 15,619,000 15,207,000 9,470,000 8,373,000 25,615,000 24,570,000 June 14,370,000 14,402,000 8,006,000 8,148,000 23,269,000 23,230,000 July 13,126,000 14,071,000 6,967,000 8,284,000 23,864,000 25,601,000 August 14,250,000 16,393,000 5,846,000 7,271,000 21,767,000 25,047,000 September 14,324,000 15,709,000 9,021,000 7,767,000 24,169,000 23,334,000 October 15,191,000 14,723,000 7,041,000 7,111,000 26,380,000 24,850,000 November 13,756,000 13,483,000 6,167,000 7,234,000 23,850,000 23,639,000

| Layers sold for slaughter | Layers rendered, died, destroyed, composted, or disappeared for any other reason (other than sold) | Total layers died for any reason | Pullets added | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 |

| 175,048,000 | 177,579,000 | 89,757,000 | 93,064,000 | 264,805,000 | 270,643,000 | 287,468,000 | 289,780,000 |

2014 Layer Hen Death Interval in the U.S.

270,643,000 hens/year * year/31,536,000 seconds = 8.58 hens/second = 1 hen/0.12 seconds

Number of Male Chicks Hatched/Culled Per Year

It can be assumed that for each layer pullet added to the flock, a male chick was hatched. That is, there were around 289,780,000 male chicks hatched in 2014 (see Total Number Slaughtered, Lost, and Added — United States: 2013 and 2014 above), and it can be assumed that nearly 100% of those were culled.

2014 Male Chick Cull Interval in the U.S.

289,780,000 chicks/year * year/31,536,000 seconds = 9.19 chicks/second = 1 chick/0.11 seconds

Quality of Meat from Spent Hens

"Traditionally, processors have bought spent fowl from egg producers and slaughtered them for use in food products such as soups and further processed meats. Egg companies were able to put the income from the sale of these birds against the cost of replacement chicks. Recently this market for spent fowl has declined. The modern White Leghorn hen is a small-framed chicken with a minimum of muscle mass and yields little meat upon processing. Moreover, the bones of spent layers often shatter during slaughter. When this happens, bone fragments can penetrate the meat and reduce its value as a marketable product. The expansion in numbers of broiler breeders to keep pace with the enormous growth of the broiler industry has also affected the market for spent commercial layers. A broiler breeder hen is larger than a White Leghorn hen and yields considerably more meat. The availability of spent broiler breeders with the relative efficiencies to be had processing these buds, as well as the increased use of broiler meat in products that once used fowl meat, have led processors to restrict their commitments to buy spent laying hens."